Here's How to Survive a Nuclear War

It's technically possible, but it won't be easy

“It does not do to leave a live dragon out of your calculations, if you live near him.” — JRR Tolkein

A few years ago, while making a documentary on human trafficking, my wife and I visited Switzerland.

When we arrived at our host’s house, the first thing he did was take us down into the basement to show us his nuclear bunker.

It was fantastic.

Concrete walls… several weeks of food… a nice little library of books… a totally sealable door. It even had a well in the concrete floor so they wouldn’t run out of freshwater.

I slept very well that night.

I later learned that those forward-thinking Swiss have 360,000 communal shelters — enough nuclear shelters for their entire population. (The actual coverage is 114% of the population, and the biggest can hold 20,000 people.)

As Vladimir Putin continues his slow grind into Ukraine and threatens nuclear annihilation on his growing list of enemies, let’s take a few moments to review what it will take for humanity to survive a global nuclear war.

The first thing to understand

Not all nuclear events are the same.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki aren’t like Chernobyl.

While Chernobyl is still so radioactive that it has a 1,040-mile exclusion zone, Nagasaki is safe and healthy, with a thriving population of over 429,000. Hiroshima, meanwhile, is about to hit 1.2 million.

Here’s Nagasaki today:

Beautiful, right?

Nuclear bombs are horrible and they kill a huge amount of people, but unbelievably, they are survivable.

76% of Hiroshima’s buildings were destroyed, but 60% of the people in Hiroshima survived, as did nearly 70% of people in Nagasaki.

I don’t know if this comforts you or not, but there’s a strong chance you will actually survive a nuclear attack on your city if you’re outside the epicenter.

For example, the closest known survivor of the Hiroshima bomb was Eizō Nomura, who was in the basement of a reinforced concrete building just 560 feet from the hypocenter.

Nearly 200 unlucky (or extremely lucky) people survived both atomic bombs.

As of 31 March 2021, 127,755 hibakusha (Japanese nuke survivors) are still alive.

Global thermonuclear war

If Vladimir Putin nukes a major city (likely Berlin to start), the absolute best-case scenario would be for the rest of the world to turn the other cheek, take the loss, go into mourning, and not retaliate. As Gandhi said, “An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind.” But non-retaliation is not America’s way, and ‘Murica would rather take the whole world to hell than forgive a heinous enemy and find another path to peace.

So what’s the worst-case scenario?

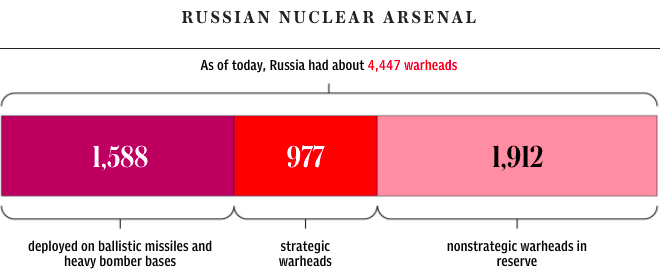

Well, there are currently <15,000 nukes in this idiotic Boomer-run world. Most of them are controlled by the US and Russia, and that’s where most of the nuclear drops will take place. Still, if the average nuke has a 3-mile blast radius (28.27 square miles), that’s “only” ~424,000 square miles. In other words, if every single nuke on earth was dropped, it means just 0.017205867% of Earth’s habitable land would be inside a guaranteed-kill blast radius.

And remember, half of these nukes will never be fired because most of America’s and Russia’s nukes are just pointed at each other’s nukes. If, after a war of nuke-cancellation, we’re actually talking about ~7,500 nukes, and the majority of those rain down on America and Russia, there’s a chance that Africa, South America, and Oceania will be relatively blast-free.

Granted, all of planet Earth will be in the disastrous fallout zone, but this is technically survivable.

To be sure, if you’re within a 3-mile radius of the epicenter of a nuke drop, you’re just plain dead. But then you have nothing to worry about. You’ve been instantly and painlessly vaporized into atomic dust by heat hotter than the sun. Lucky you.

But for the majority of people outside of any number of nuke epicenters, there are things we can do to seriously increase our chances of survival.

Let’s dig into your first 11 life-saving steps.